This is in contrast to the current (v.2.0.0) weather system of Flightgear where weather changes affect the weather everywhere in the simulated world and are (with few exceptions) not tied to specific locations. In such a system, it is impossible to observe e.g. the approach of a rainfront while flying in sunshine.

The local weather package ultimately aims to provide the functionality to simulate such local phenomena. In version 0.8, the package supplies various cloud placement algorithms, as well as local control over most major weather parameters (wind, visibility, pressure, temperature, rain, snow, thermal lift, turbulence...) through interpolation routines and event volumes. The dynamics of the different systems is tied together - clouds and weather effects drift in the specified wind field. The package also contains a fairly detailed algorithm to generate convective clouds and thermals with a realistic distribution. Unfortunately, as of v0.8, there is no interaction yet between the windfield and the cloud-generating algorithms, i.e. while the placement algorithms create a realistic configuration of thermals and convective clouds, the wind will simply move this configuration, not create, destroy or move clouds in altitude dynamically (which would be realistic).

For long-range flights, the system automatically provides transitions between different weather patterns like fronts and low and high pressure areas. However, basically all features currently present can and will eventually be improved.

This adds the items Local Weather and Local weather tiles to the Environment menu when Flightgear is up. Most of the basic functionality is contained in local_weather.nas which is loaded at startup and identifies itself with a message, but does not start any functions unless called from the GUI.

The first menu contains the low level cloud placement functions. Its purpose is mainly for developing cloud patterns without having to resort to re-type the underlying Nasal code every time. Currently five options are supported: Place a single cloud, Place a cloud streak, Start the convective system, Create barrier clouds and Place a cloud layer.

The algorithm as called from the menu assumes that the streak center is the current position. x and y are the primary grid directions. number x (y) are the number of clouds to be placed in these directions, Delta x (y) the spacing between clouds along these directions. x (y) edge describes the fraction of the pattern to be taken by one border filled with small clouds. Since the pattern has borders from two sides, a fraction of 0 means that only large clouds are placed, a fraction of 0.5 that only small clouds are placed, anything inbetween corresponds to a transition. Dir is an angle by which the whole pattern is rotated. Finally, Triang. allows the distortion of the pattern into a trapezoid shape in which one side is by Triang. larger than the other.

The pattern can then be randomized in x, y and altitude. Basically, specifying no grid spacing but large randomization scales corresponds to a random placement of clouds in the sky, whereas randomization scales lower than the grid spacing preserve the grid structure, and the algorithm allows to interpolate between these extremes.

Unless 'Terrain presampling' is active, clouds are placed in a constant altitude alt in a tile with given size where the size measures the distance to the tile border, i.e. a size parameter of 15 km corresponds to a 30x30 km region. When 'Terrain presampling' is selected, the distribution of clouds in altitude is determined by a more complicated algorithm described in the appendix. Clouds are placed with constant density for given terrain type, so be careful with large area placements! strength is an overall multiplicative factor to fine-tune.

Currently, the algorithm does not check for a barrier upstream - this will change in future versions. The ufo is a good way to explore the results of the algorithm by simply flying to a suitable location and calling it there for a relatively small region.

If rainflag is set to 1, the system will also place external precipitation models (i.e. visible rain layers), roughly at the transition between edge and core of the cloud placement region with a density given by rain dens.. The system will however not place an effect volume which would lead to the actual simulation of rain below the layer - this must be done separately by the user.

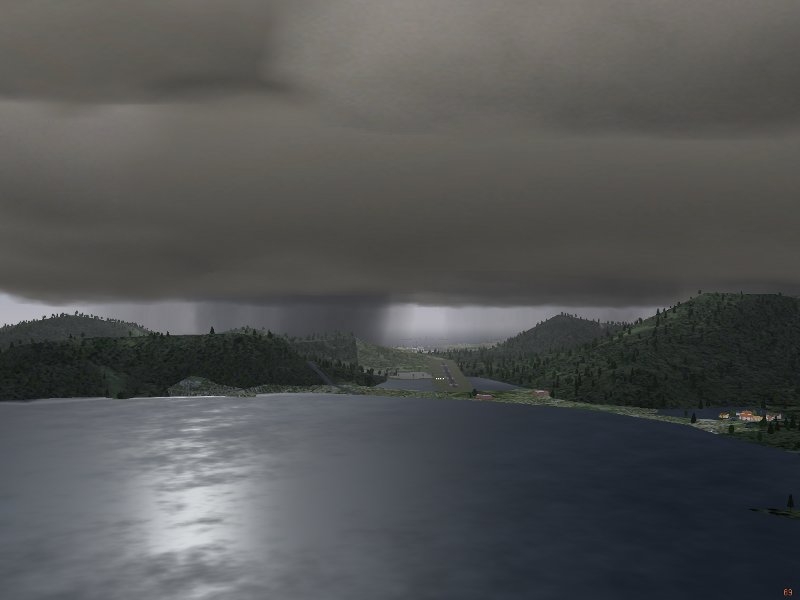

The picture illustrates the result of a layer generation call for Nimbostratus clouds with precipitation models.

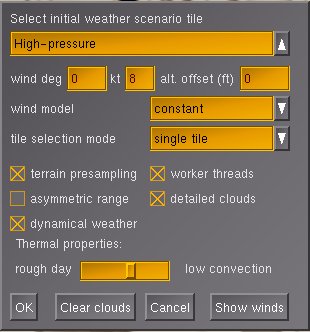

The dropdown menu is used to select the type of weather tile to build. The menu contains two groups of tiles - the first are classified by airmass, whereas the last two are scenarios intended for soaring.

Below are entries for three parameters. The first two are the simplified version of wind direction and speed for the user who is not interested in specifying many different wind interpolation points. The third parameter, the altitude offset, is to manually adjust the altitude level of clouds in the absence of terrain presampling. Cloud layer placement calls are then specified for absolute altitudes and calibrated at sea level. As a result, layers are placed too low in mountainous terrain, hence the need for an offset. The offset may at present also be useful for dynamical weather, as convective clouds with terrain presampling follow terrain altitude, which looks strange when the clouds are allowed to drift in the wind without altitude correction.

The dropdown menu for the wind contains various models for how the windfield is specified which require a different amount of user-specified input. The options are described further down when the windfield modelling is described in more detail.

The dropdown menu for the tile selection mode controls the long-range behaviour of weather. It specifies according to what rules tiles are automatically generated once the aircraft reaches the border of the original tile. The option 'single tile' creates a single weather tile as specified without automatic generation of further tiles. The option 'repeat tile' creates new tiles of the same type as the originally selected tile. This does not mean that weather will be unchanged during flight, as both parameters like pressure, temperature and visibility as well as the positioning of cloud banks are randomized to some degree. In addition, each tile typically contains 2-5 different cloud scenarios, so five repeated generations of 'low-pressure-border' tiles may never result in the same arrangement of cloud layers. Necertheless, the option will keep weather conditions roughly the same. This is different with the (somewhat optimistically named) 'realistic weather'. This option allows transitions between different airmasses, thus one may select 'low-pressure-core' initially, but as the flight goes on, eventually a region of high pressure and clear skies may be reached. Currently this change between airmasses does not include transitions across fronts. Moreover, it does not cover transitions to arctic or tropical weather conditions - those will be covered in a future release. Note that 'realistic weather' does not work for the two soaring scenarios, 'repeat tile' does not work for any tile which is part of a front.

The final option, 'METAR', generates weather according to parsed METAR information. This information must be made available in the property tree. Currently this is not done automatically and the METAR system does not work with real-weather-fetch, this needs some work on the Flightgear core.

Below the menu are five tickboxes. 'Terrain presampling' finds the distribution of altitude in the terrain before placing a cloud layer. As a result, the layers or clouds are automatically placed at the correct altitude above ground in level terrain. In mountain regions, cloud placement is fairly tricky, and the algorithm analyzes quantities like the median altitude to determine what to do. The appendix contains a detailed description of the algorithm. If the box is ticked, the altitude offset specified above is not parsed.

'Worker threads' is an option to distribute the work flow. Usually, the local weather package will compute a task till it is done before starting the next. Thus, creating a new weather tile may lead to a few seconds freeze, before Flightgear continues normally. With 'worker threads' selected, computations will be split across several frames. The advantage is that Flightgear stays responsive during loading and unloading of weather tiles, and in general the flight continues smoothly, albeit with reduced framerate. However, selecting this option does not guarantee that an operation is finished by the time another is beginning - thus there may be situations in which the loading of a new tile blocks unloading of an old one and so on, in essence leading to processes competing for access to the weather array, resulting in an extended period of very low framerates. Dependent on system performance, this may or may not be acceptable to the user. 'asymmetric range' is an experimental performance-improving option (see below). Finally, 'detailed clouds' will change the technique for generating Cumulus clouds from a multilayer model to multiple cloudlets filling a box. This improves the visual appearance of the clouds significantly, albeit at the expense of a (significant) loss of framerate. Rendering multiple tiles of dense Cumulus development with detailed clouds will quite possibly freeze even a powerful system.

The option 'dynamical weather' ties all clouds and weather effects to the windfield. If that option is not chosen, the wind is still generated according to the chosen model, but only felt by the aircraft. This makes e.g. soaring unrealistic, as the aircraft continuously drifts out of a static thermal below a static cap cloud. When 'dynamical weather' is selected, aircraft, cloud and thermal are all displaced by the wind.

The slider 'Thermal properties' is only relevant for soaring scenarios. It governs the rato of maximum lift to radius of a thermal. A setting close to 'low convection' creates large thermals with relatively small lift and virtually no turbulence, a setting close to 'rough day' creates very narrow, turbulent thermals with large lift. Unless thermals are placed, no other weather tile is affected by the settings.

The button 'Show winds' brings up the detailed wind menu which is needed for the wind models 'aloft interpolated' and 'aloft waypoints':

For 'aloft interpolated', the menu is used by inserting wind direction and speed for all given altitudes. After 'Okay', the specified values are used. For 'aloft waypoints', the same info must be supplied for a series of waypoints. First, the latitude and longitude has to be inserted, afterwards the aloft winds for that point below. The button 'Set waypoint' commits the windfield as specified in the menu for this position into memory. For orientation, the number of points inserted is counted on the lower right. 'Clear Waypoints' removes all information entered so far. Note that 'Okay' does not commit the data for a waypoint.

In principle, the waypoint information inserted so far can be seen using the property browser. It is stored under /local-weather/interpolation/wind[n]/.

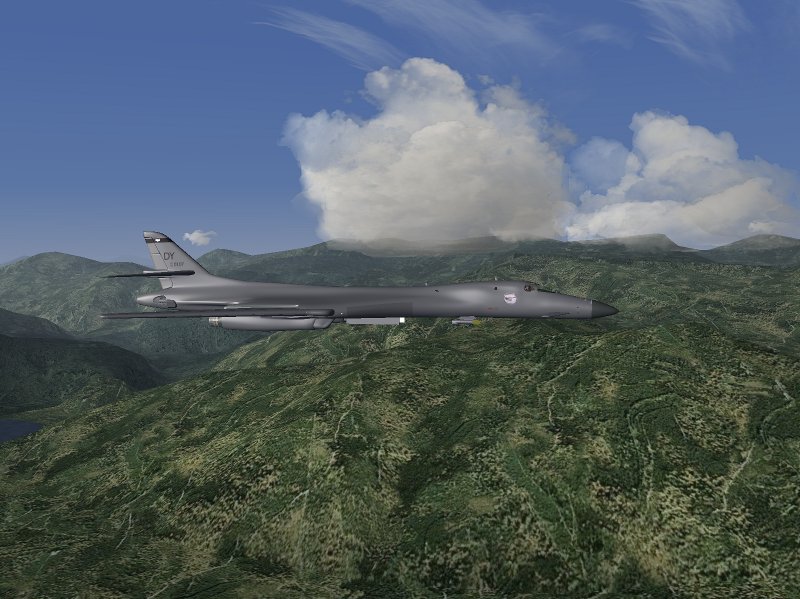

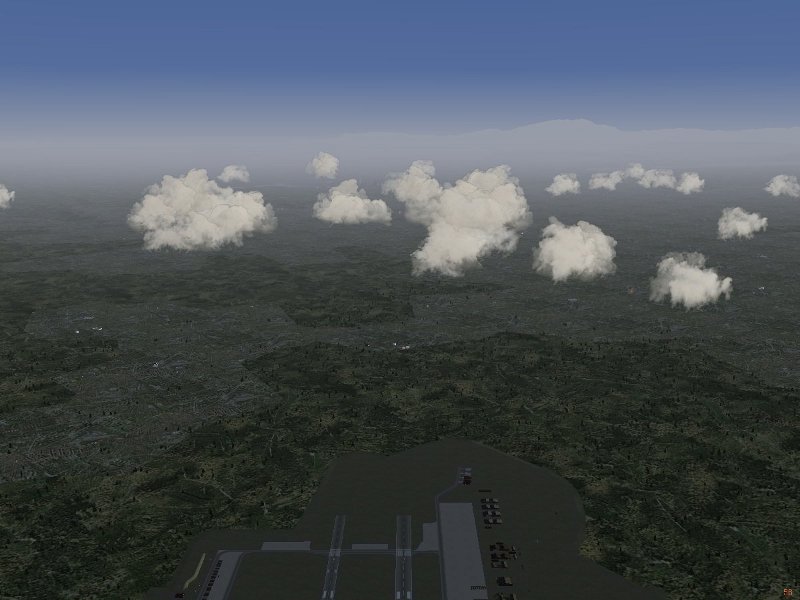

The following pictures show the results of tile setups 'Low-pressure-border' and 'High-pressure-border':

These are rendered by a different technique: While the default Cumulus models consist of multiple layers rotated around the center of the model, the detailed Cumulus clouds consist of multiple (up to 24) individual cloudlets, rotating each around its own center, randomly distributed into a box. This not only improves the visual appearance, but also leads to a more realistic distribution of cloud sizes and shapes in the sky. In addition, when circling below the cloud (as done when soaring) the effect of the cloudlet rotation is less pronounced. The price to pay is that rendering detailed clouds costs about a factor 4 more performance, so they may not be suitable for all systems.

More complex clouds are rendered in sandwitched layers of several different textures. An example are Cumulonimbus towers, which use diffuse textures on the bottom, changing to more structured textures in the upper part of the cloud. With up to 2000 cloudlets, skies with multiple thunderstorms may not render with sufficient framerates on every system.

The general problem is finding a good balance between spending a lot of CPU time to make a single cloud model appear perfect, and the performance degradation that occurs if hundreds of clouds are placed in the sky. The basic aim is to provide realistic appearance for clouds from a standard view position (in cockpit looking forward), to retain acceptable appearance from other positions and to allow large cloud layers.

Currently all clouds which need to be rotated are treated in the Shaders using a view-axis based rotation by two angles. This generally looks okay from a normal flight position, but rapid change of the view axis (looking around), especially straight up or down, causes unrealistic cloud movement. Any static picture of clouds however is (almost) guaranteed to look fine. This means that shader effects need to be 'on' in order to see most of the clouds.

The idea is that the interpolation system takes care of slow, large-distance scale changes of weather whereas the effect volume system models rapid, small-scale changes. Thus, the gradual drop in visibility when flying into a more humid air mass is dealt with by the interpolation system whereas the sudden drop in visibility when entering a cloud is modeled as an effect volume. It doesn't make sense to have both systems available for all weather parameters, for example pressure can't change suddenly and discontinuously. Consequently the effect volume system does not support pressure.

While the station concept is designed to support easy connection with weather updates from real METAR stations, stations do not need to be real stations, and each weather tile creation call by default writes its own station at the center of the tile, so weather tiles can be different and the weather will change smoothly between them.

Technically, the structure of the interpolation system means that while it is running, neither setting weather parameters in the standard menu nor changing visibility using the z-key will have an effect - any setting made there will be overwritten periodically. Only changing the relevant properties (see below) will have the desired effect.

Effect volumes may be nested, and they may overlap. The rules determining their behaviour can be summarized as follows: 1) there is no cross-talk between weather parameters, i.e. an effect volume specifying visibility is never influenced by one specifying pressure, regardless if they overlap or not. 2) when an effect volume is entered, its settings overwrite all previous settings 3) when an effect volume is left, the settings are restored to what the interpolation routine specifies if no other effect volumes influence the weather parameter, to the values as they were on entering the volume when the number of active volumes has not changed between entering and leaving the volume (i.e. when volumes are nested) or nothing happens if the number of active volumes has increased (i.e. when volumes form a chain). This is illustrated in the following figure:

Volumes 2 and 3 are nested inside volume 1, therefore all settings of 2 overwrite those of 1 when 2 is entered and are restored to 1 when region 2 is left directly into 1. Region 4 is a chain, and as such ill defined: When one leaves 2 into 4, the settings of volume 3 are used (because later definitions overwrite earlier ones). When one now leaves 4 into 3 (and hence leaves 2), it would be wrong to restore to the values on entry of 2 (i.e. the properties of 1), as 3 is still active. But the active volume count has changed, so leaving 4 into 3 does not lead to any changes. The reason why 4 is still ill-defined is that what weather is encountered in 4 depends on the direction from which it is entered - when it is entered from 2, it has the properties of 3, whereas when it is entered from 3, it has the properties of 2.

Effect volumes are always specified between a minimum and a maximum altitude, and they can have a circular, elliptical and rectangular share (the last two rotated by an angle phi). Since it is quite difficult to set up event volumes without visual reference and also not realistic to use them without the context of a cloud or precipitation model, there is no low-level setup call available in the menu. Effect volumes can be created with a Nasal call

create_effect_volume(geometry, lat, lon, r1, r2, phi, alt_low, alt_high, vis, rain, snow, turb, lift, lift_flag);

where geometry is a flag (1: circular, 2: elliptical and 3: rectangular), lat and lon are the latitude and longitude, r1 and r2 are the two size parameters for the elliptic or rectangular shape (for the circular shape, only the first is used), phi is the rotation angle of the shape (not used for circular shape), alt_low and alt_high are the altitude boundaries, vis, rain, snow, turb and lift are weather parameters which are either set to the value they should assume, or to -1 if they are not to be used, or to -2 if a function instead of a parameter is to be used. Since thermal lift can be set to negative values in a sink, a separate flag is provided in this case.

In version 0.8, thermal lift is implemented by function. There is no easy way to implement any weather parameter by function in an effect volume, as this requires some amount of Nasal coding.

It is quite clear that the wind model within local weather has to be an approximation to the real situation. First, the windfield is assumed to always have horizontal components only - vertical air movement is simulated on top of the wind field by ridge lift generated from the Flightgear core and by thermals and turbulence as effect volumes.

In the horizontal windfield, aloft and bounday layers need to be distinguished. The aloft wind layers are high enough so that they do not interact with the terrain (and hence can be specified as a function of altitude above sea level), the low region where the aloft winds experience friction by interaction with the terrain and are slowed down constitutes the boundary layer. The boundary layer hence needs to be defined as a function of altitude above ground - it shifts as the elevation shifts. The size of the boundary layer, as well as its capacity to slow down aloft winds, depends on the roughness of the terrain. Over the open sea, the boundary layer is typically as small as 150 ft, while over rough terrain it can extend up to several hundred ft.

When the option 'dynamical weather' is active, clouds and effect volumes move with the wind. Due to performance reasons, only clouds in the field of view are processed in each frame. As an efficient way to do this, a quadtree structure is used. However, this has the side effect that all clouds inside a tile need to be moved with the same windspeed (otherwise they would over time drift out of the position where the quadtree expects to find them). Since thermals and their cap clouds should not drift apart, also weather effects are moved with the same windspeed inside each tile. In the following, this is referred to as 'tile wind speed'. The tile wind speed always corresponds to the lowest aloft layer windspeed. The reason why this is considered acceptable is that at the same altitude for different positions inside a tile, the correct windspeed is at most a few kt different from the tile windspeed, and this is impossible to see visually. At high altitudes, the true wind is very different from the speed at which clouds are moved, but without reference and from fast-moving planes, the error is again very hard to see. However, with e.g. a hot air balloon, the fact that at high altitudes clouds are not moved with the high-altitude windspeed would be quite apparent.

Dependent on how detailed the wind field should be specified, what the pilot aims to do and how much user control is desired, there are several options to model the wind.

The local-weather folder contains various subdirectories. clouds/ contains the record of all visible weather phenomena (clouds, precipitation layers, lightning...) in a subdirectory tile[j]/cloud[i]/. The total number of all models placed is accessible as local-weather/clouds/cloud-number. Inside each cloud/ subdirectory, there is a string type specifying the type of object and subdirectories position/ and orientation which contain the position and spatial orientation of the model inside the scenery. Note that the orientation property is obsolete for clouds which are rotated by the shader.

The local-weather/effect-volumes/ subfolder contains the management of the effect volumes. It has the total count of specified effect volumes, along with the count of currently active volumes for each property. If volumes are defined, their properties are stored under local-weather/effect-volumes/effect-volume[i]/. In each folder, there are position/ and volume/ storing the spatial position and extent of the volume, as well as the active-flag which is set to 1 if the airplane is in the volume and the geometry flag which determines if the volume has circular, elliptical or rectangular shape. Finally, the effects/ subfolder holds flags determining of a property is to be set when the volume is active and the corresponding values. On entry, the effect volumes also create a subfolder restore/ in which the conditions as they were when the volume was entered are saved.

local-weather/interpolation/ holds all properties which are set by the interpolation system, as well as subfolders station[i]/ in which the weather station information for the interpolation are found and subfolders wind[i] where wind information in the case of 'aloft interpolated' or 'aloft waypoints' is stored. Basically, here is the state of the weather as it is outside of effect volumes. Since parameters may be set to different values in effect volumes, the folder local-weather/current/ contains the weather as the local weather system currently thinks it should be. Currently, weather is actually passed to the Flightgear environment system through several workarounds. In a clean C++ supported version, the parameters should be read from here.

local-weather/tiles stores the information of the 9 managed weather tiles (the one the airplane is currently in, and the 8 surrounding it). By default each directory contains the tile center coordinates and a flag if it has been generated. Tiles are not generated unless a minimum distance to the tile center has been reached. Once this happens, the tile type is written as a code, and the cloud, interpolation and effect volume information corresponding to the tile is generated.

local-weather/METAR is used to store the METAR information for the METAR based tile setup. This must include latitude, longitude and altitude of a weather station, temperature, dewpoint, pressure, wind direction and speed, rain, snow and thunderstorm information as well as cloud layer altitude and coverage in oktas. Any properties set here will be executed when 'METAR' is selected as tile selection mode as long as local-weather/METAR/available-flag is set to 1 (this flag is set to zero whenever a tile has been created from METAR info to indicate that the information has been used, so if the user wants to reuse the information, then the flag must be reset).

The first important call sets up the conditions to be interpolated:

set_weather_station(latitude, longitude, visibility-m, temperature-degc, dewpoint-degc, pressure-sea-level-inhg);

The cloud placement calls should be reasonably familiar, as they closely resemble the structure by which they are accessible from the menu. Note that for (rather stupid reasons) currently a randomize_pos call must follow a create_streak call.

If the cloud layer has an orientation, then all placement coordinates should be rotated accordingly. Similarly, each placement call should include the altitude offset. Take care to nest effect volumes properly where possible, otherwise undesired effects might occur...

To make your own tile visible, an entry in the menu gui/dialogs/local_weather_tiles.xml needs to be created and the name needs to be added with a tile setup call to the function set_tile in Nasal/local_weather.nas.

At the core of the convective algorithm is the concept of locally available thermal energy. The source of this energy is solar radiation. The flux of solar energy depends on the angle of incident sunlight with the terrain surface. It is possibly (though computationally very expensive) to compute this quantity, but the algorithm uses a proxy instead. The daily angle of the sun at the equator assuming flat terrain is modelled as 0.5 * (1.0-cos(t/24.0*2pi)) with t expressed in hours, a function that varies between zero at midnight and 1 at noon. There is a geographical correction to this formula which goes with cos(latitude), taking care of the fact that the sun does not reach the zenith at higher latitudes. Both the yearly summer/winter variation of the solar position in the sky and the terrain slope are neglected.

However, the incident energy does not equal the available energy, since some of this energy is reflected back into space, either by high clouds, or by the terrain itself. The reflection by high clouds is not explicitly included in the algorithm - but since in creating a weather tile, one must setup both the high altitude clouds and the convective system, it can easily be included approximately by calling the convective system with a strength that is reduced according to the density of high-altitude clouds. The reflection by the terrain is encoded in the probability p that a given landcover will lead to a thermal. p ranges from 0.35 for rock or concrete surface which heat very well in the sun to 0.01 over water or ice which reflect most of the energy back into space.

The algorithm now tries to place a number n of clouds in a random position where n is a function of the user-specified strength of development, modified by the daily and geographical factors as described above. However, a cloud is only placed at a position with probability p, so a call to the convective system over city terrain will lead to significantly more clouds than a call with the same strength over water.

The next task is to determine how the available thermal energy is released in convection across different thermals. There can be for example many weak thermals, or few strong thermals for the same energy. The empirical observation is that the number of thermals and clouds peaks around noon, whereas the strength of thermals peaks in the afternoon. The algorithm thus assigns a strength 1.5 * rand() + (2.0 * p)) to each cloud, which is again modified by a sinusoidal function with a peak shifted from noon to 15:30.

Based on this strength parameter s, a cloud model is chosen, and the maximal thermal lift (in ft/s) is calculated as 3 + 1 * (s -1) (note that this means that not every cloud is associated with lift). By default, the radius of thermals is assumed to range from 500 to 1000 m. The slider 'thermal properites' in the menu allows to modify the balance between radius and lift from these values. Since the flow profile in a thermal is approximately quadratic, requiring the same flux means that increasing the maximal lift by a factor f leads to a radius reduced by 1/f. Moving the thermal properties slider to 'rough day' thus generates narrow thermals with large maximal lift and sink (which are more difficult to fly), moving it to low convection instead generates large thermals with weak lift.

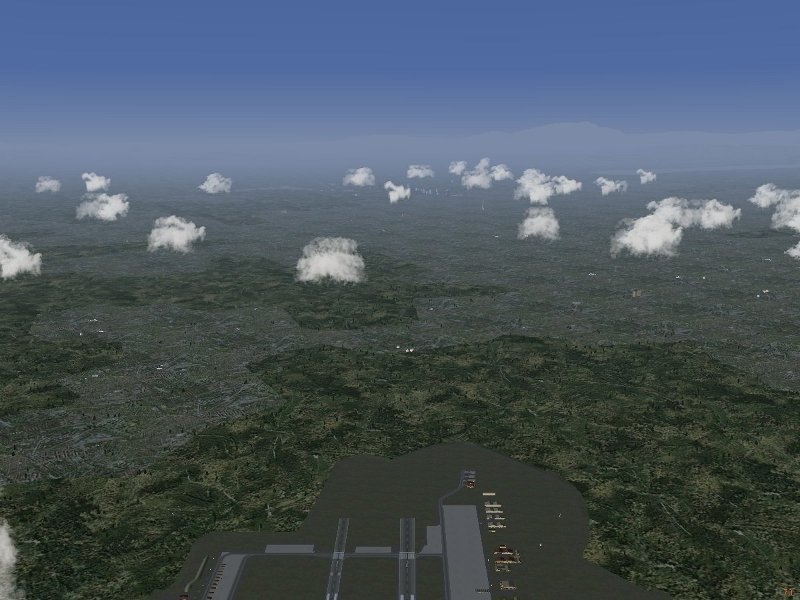

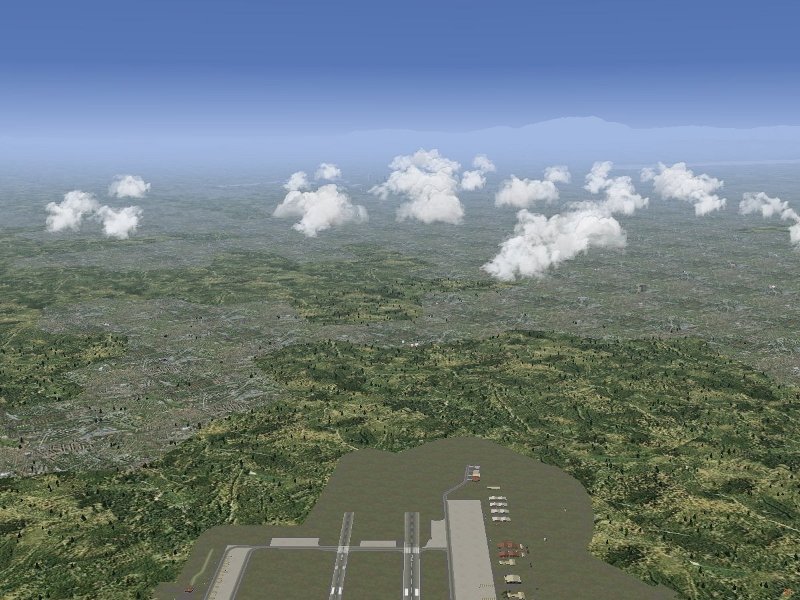

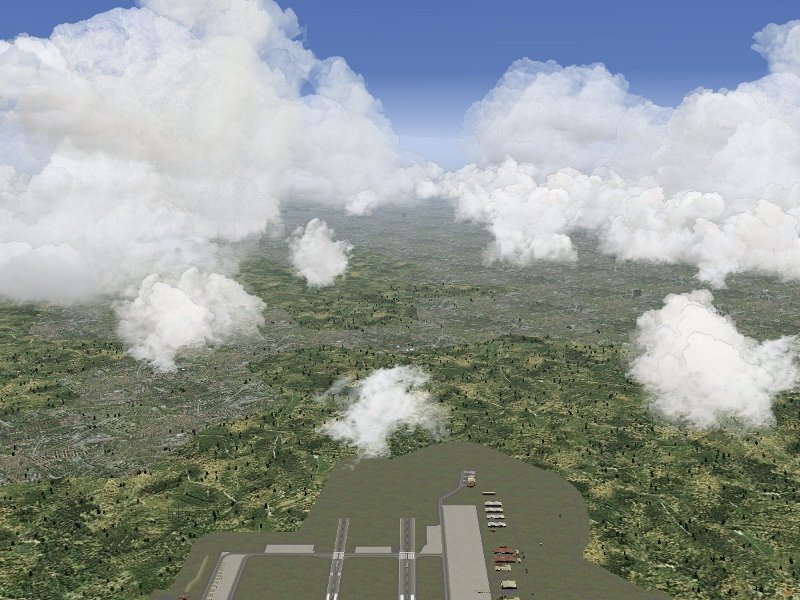

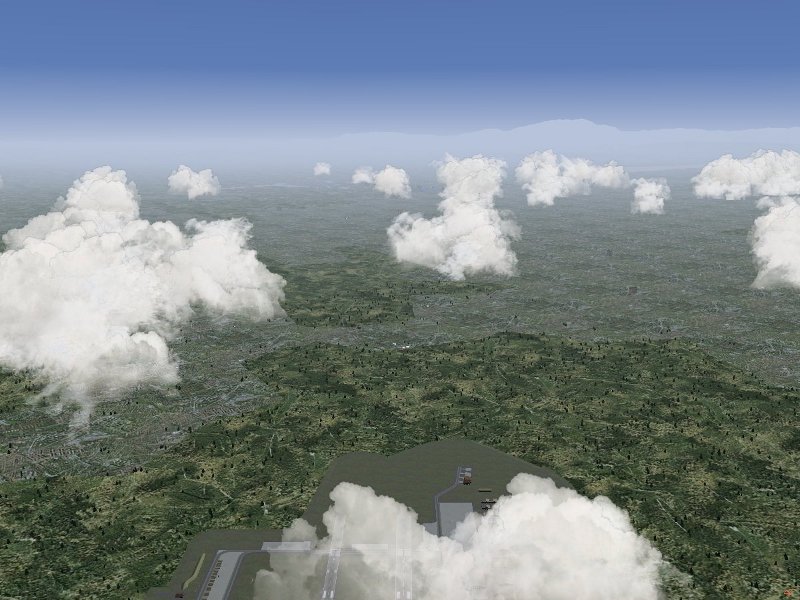

The following series of pictures, taken over KLSV (Nellis AFB, Las Vegas) illustrates the algorithm at work.

At 7:00 am, the thermal activity is weak, and there is no lift available in thermals yet.

Some activity starts around 10:00 am the average available lift is 0.3 m/s, the more active clouds tend to be above city terrain.

At 12:00 noon, the maximal cloud number is reached. The average available lift is 1 m/s, in peaks up to 2 m/s.

The maximum of lift strength is reached close to 15:00 pm. The average lift is now 1.5 m/s, in peaks up to 3 m/s, and the strong convection leads to beginning overdevelopment, some clouds reach beyond the first inversion layer and tower higher up. At this point, the clouds may also overdevelop into a thunderstorm (which is not modelled explicitly by the convective algorithm as it requires somewhat different modelling, but is taken into account in the weather tiles).

At 17:30 pm, the lift is still strong, 1.5 m/s on average and 2.5 m/s in peaks, but compared with the situation at noon, there are fewer clouds with stronger lift.

At sunset around 19:00 pm, the number of clouds decreases quickly, but there is still a lot of residual thermal energy (the ground has not cooled down yet), therefore thermal lift of on average 1 m/s is still available even without solar energy input.

While not accurate in every respect, the model works fairly well to reproduce the actual time dependence of convective clouds and thermal lift during the day.

In nature, what determines the altitude of various clouds are the properties of air layers. In general, clouds become visible at the condensation altitude, i.e. when temperature and dew point merge and the relative humidity of air exceeds 100%. In conditions where there is a lot of vertical air movement (i.e. for Cumulus clouds), the conditions are much more local than in situations with lack of vertical movement (i.e. for layered clouds).

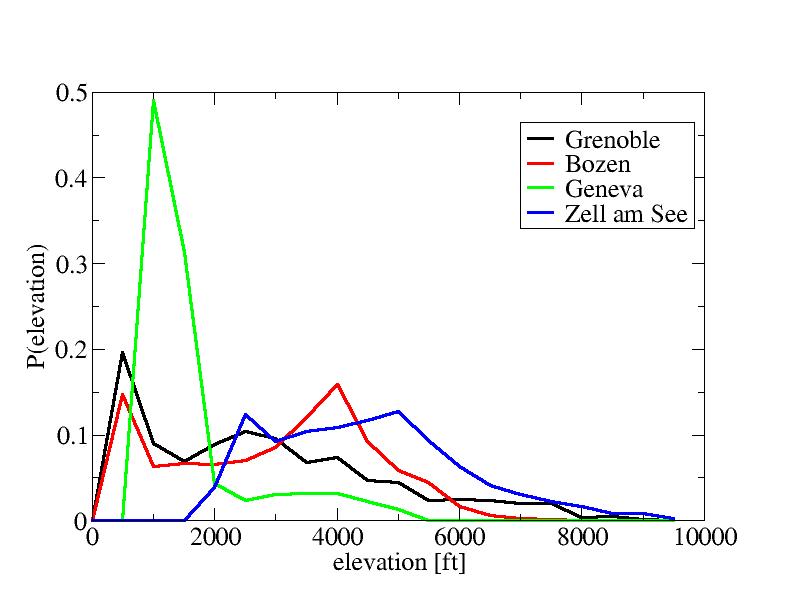

In the algorithm, various proxies for the structure of air layers and hence the condensation altitude are used. It is assumed that air layers must follow the general slope of the terrain (because there is nowhere else to go), but can (at least to some degree) flow around isolated obstacles. To get the general layout of the terrain, the algorithm first samples the altitude of an 80x80 km square around the 40x40 weather tile to be created. The choice of a larger sampling area reduces the sensitvity of the outcome to purely local terrain features and prevent pronounced transitions from one tile to the next. The result of this sampling is a distribution of probability to find the terrain at a given altitude:

For instance, the terrain around Geneva is mostly flat around 1000 ft (where the peak of the distribution lies) with some mountains up to 4500 ft nearby. Based on such distributions, the algorithm next determines the minimum altitude alt_min, the maximum altitude alt_max, the altitude below which 20% of the terrain are found alt_20 and the median altitude below which 50% of the terrain are found alt_med.

Cumulus clouds are always placed at a constant altitude above alt_20. This is done to ensure gorges and canyons do not provide a minimum in otherwise flat terrain so that clouds appear down in the gorge as opposed to on the rim where they would naturally occur. Basically, layers are assumed not to trace too fine structures in the terrain, so at least 20% of the terrain are required. In the test case of Grand Canyon, the algorithm correctly places the clouds at rim altitude rather than down in the canyon:

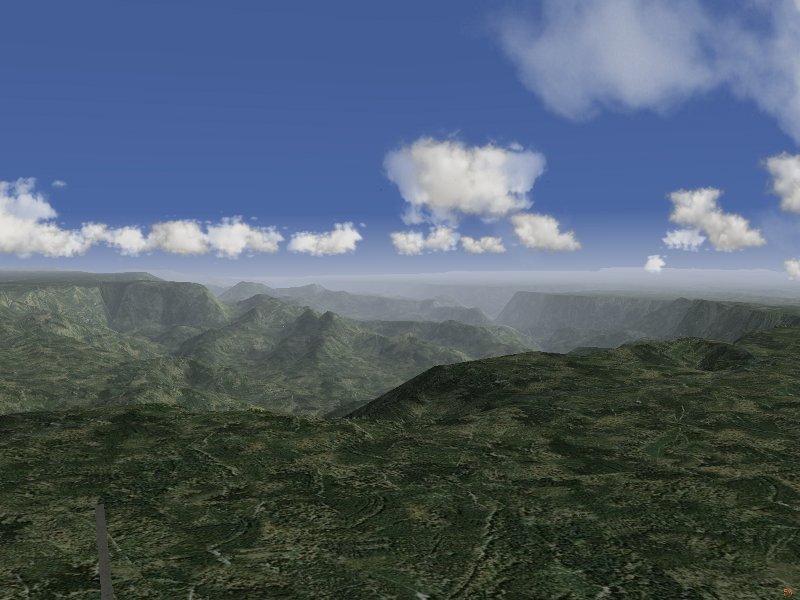

However, convective clouds are given some freedom to adjust to the terrain. The maximally possible upward shift is given by alt_med - alt_20. This is based on the notion that above alt_med, the terrain is not a significant factor any more because the air can simply flow around any obstacle. However, this maximal shift is not always used - if the cloud is placed far above the terrain in the first place, it would not follow the terrain much. Thus, a factor of 1000 ft / altitude above terrain, required to be between 0 and 1, modifies the shift. As a result, a cloud layer placed high above the terrain has no sensitivity to terrain features. The result of this procedure is that clouds show some degree of following terrain elevation, as seen here in Grenoble

but they do not follow all terrain features, especially not single isolated peaks as seen here at the example of Mt. Rainier:

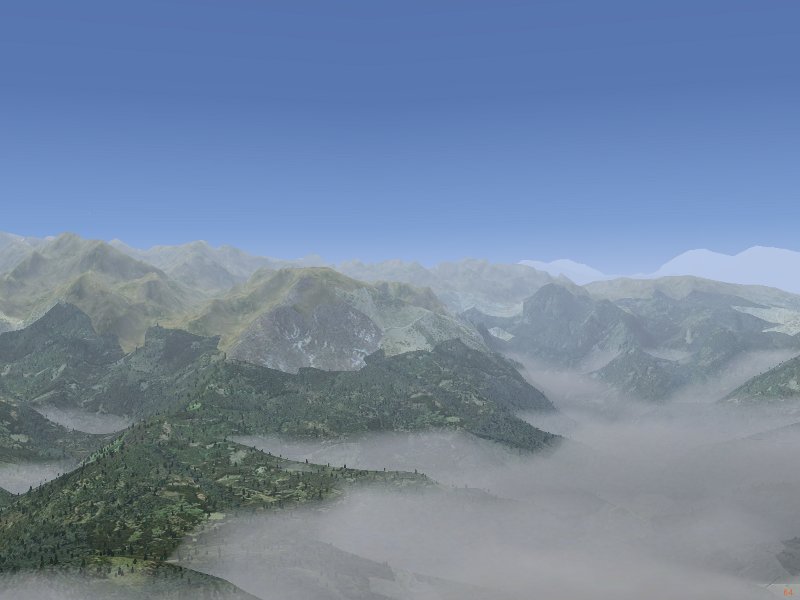

Finally, layered clouds have essentially no capability to shift with terrain elevation. Moreover, they are caused by large-scale weather processes, hence they do not usually shift upward over even large mountain massives. Currently, the model places them at 0.5 * (alt_min + alt_20) base altitude in order to retain, even in mountains, the sensitivity to the flat terrain surrounding the massiv. usually this works well, but may have a problem with gorges in flat terrain. The following picture shows a Nimbostratus layer close to Grenoble:

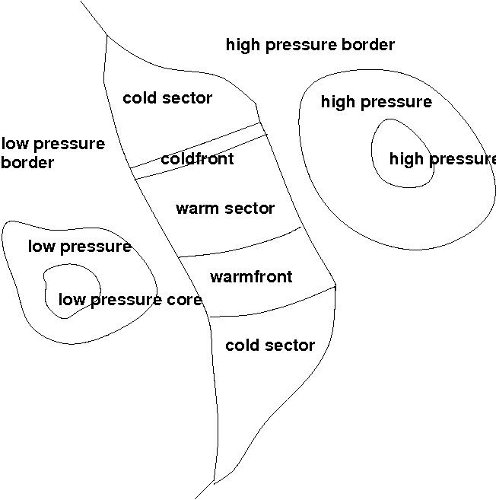

Weather tiles are classified chiefly by air pressure. What is currently in the models are three classes for a low pressure system, four different classes for the system of weather fronts and airmasses spiralling into the low pressure system and three classes for a hugh pressure system. The general rule is that low pressure tiles contain layered clouds, overcast skies and rain whereas the high pressure tiles contain clear skies and few convective clouds. The topology assumed for the weather system is apparent in the following diagram:

A transition between classes is possible whenever a class has a common border. However, if a transition actually takes place is probabilistic. Typically, the probability not to make a transition is about 80%. Since changes are only triggered for weather tiles one is actually in, the average distance over which weather patterns persist is 160 km. An exception to this are fronts - weather front tiles trigger changes based on direction rather than probability, so a warmfront will always be a sequence of 4 tiles, a coldfront will always be a small-scale phenomenon crossed within 30 km. To avoid unrealistically large changes in pressure when generating a transition and randomly sampling central pressure in tiles from two different pressure classes, a monitoring algorithm limits the pressure difference between tiles to 2 mbar and ensures a slow transition from high pressure to low pressure regions.

The weather algorithm is currently not able to handle the transition to tropical weather in the Hadley cell close to the equator, although tropical weather exists as a standalone tile and can be used in repetitive mode.

The boundary layer effectiveness, i.e. the amount of windspeed reduction at the layer bottom is assumed to vary logarithmically with thickness - thicker layers are more effective, but not dramatically so. Over open water, the layer thickness is hence about 150 ft with a maximal reduction of 10%, in deep valleys the reduction factor can be as large as 70%. The interpolation of wind reduction inside the boundary layer is done linearly.

Realistically, the boundary layer should also depend on terrain coverage. Due to the need for performance to sample terrain coverage in the vicinity of the aircraft frequently, this is currently not implemented.

Thorsten Renk, June 2010